Diana Vreeland: Immodest Style

Until the spring of 1973, it could be said that the field of costume had been a sleepy and rarified one, at least in the context of museums. An aura of antiquarianism seemed to enshroud every costume display, and they had, for all intents and purposes, no audience beyond a few specialists. Then, in that spring of 1973, Diana Vreeland joined The Metropolitan Museum of Art as Special Consultant to The Costume Institute, and almost immediately, literally from the very first of her legendary exhibitions, “The World of Balenciaga,” a large and enthusiastic audience discovered costume, not only in New York but around the world as well. Thanks to her individual achievements, there is now broad public awareness of costume. How many people are there who can actually be credited with having transformed an entire field? Diana Vreeland did that with éclat and with an uncanny sense for drama and style.

By the same token, when we extol her love of extravagance and opulence or her ability to turn even a monk’s cowl into a glamorous object, we should remember that even Mrs. Vreeland’s most successful tableaux were achieved by dint of hard work. Although she was able to make it appear to happen by the wave of a magic wand or some cabalistic incantation, she worked hard and long hours.

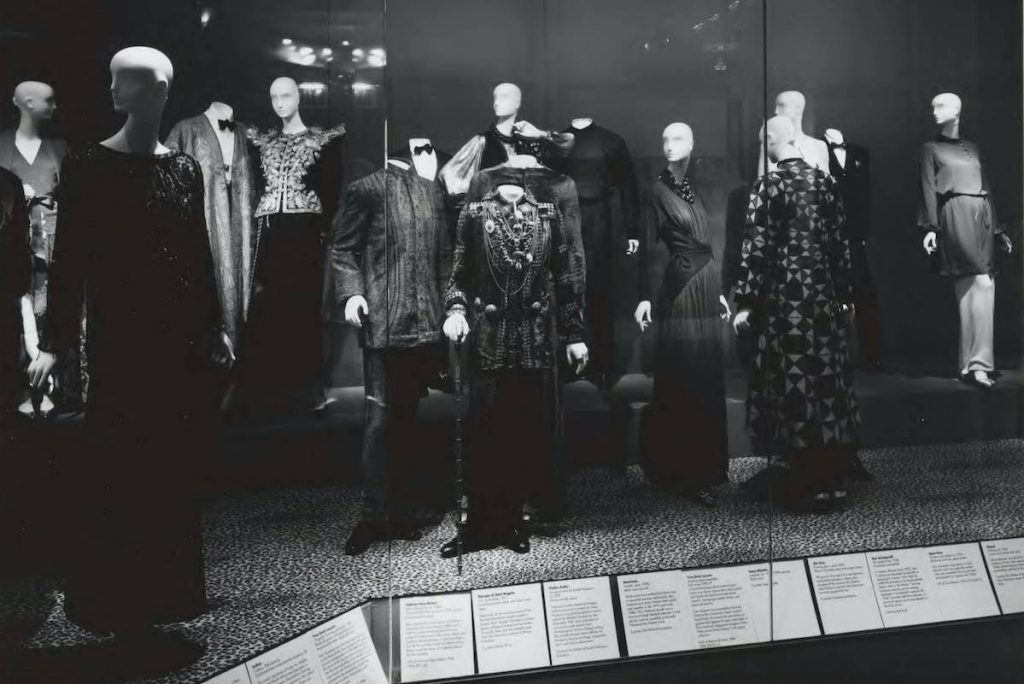

She loved the Metropolitan and was proud to be a part of it. While she got her way rather more frequently than most do here, the only powers she needed to invoke, even in her most extravagant moods, were her extraordinarily persuasive skills. The staff granted Mrs. Vreeland glossy magenta walls, headless mannequins, elephants, and carriages, because they had come to learn that her instincts were rarely wrong.

Diana Vreeland was an editor, and her approach to exhibitions reflects that fact. It was usually through a process of elimination that she arrived at the right balance in an exhibition, and to that end, she often borrowed more than she used, editing down to what was just right for the desired effect. The richness of our collections allowed her free reign to pick and choose. Indeed, one of her greatest shows was “Vanity Fair,” which was drawn entirely from the collections and for which she really was an editor. Mrs. Vreeland was amazingly visual, and it was fascinating to watch her move and adjust the costumes on the mannequins. Through the alchemy of her incredible eye, the most desultory group was turned into the most lively vignette. She knew with unfailing instinct just what adjustment would bring to life an attitude, a gesture.

While media attention naturally focused on Mrs. Vreeland’s exhibitions, I should say here that she was also a great acquisitor, and just as she maneuvered the cogwheels of the Metropolitan’s administration mostly by ignoring them and forging ahead with singular determination, her pertinacity extended as well to the wooing of donors, and The Costume Institute’s collections swelled with their gifts during her brilliant tenure.

Diana Vreeland’s legacy is, of course, a multiple one, but I think it is fair to stress that among her greatest contributions is the new freedom curators have had, because of her, to apply a new virtuosity to their displays without incurring the opprobrium of the field. Finally, it can be said with absolute assurance that the new and sustained interest in costume, the large audiences that are now attracted to it, is, for the field, Diana Vreeland’s most precious legacy.

Image provided by The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Thomas J. Watson Library