Flowers are a fashion mainstay. A flower is defined as the seed-bearing part of a plant. Sexuality lies at the core of their existence, with attraction ensured by a combination of colour, shape, texture and fragrance. Flowers, like fashion, are ephemeral, they are a luxury, seasonally determined and they inspire passion.

Flowers provide designers with a bountiful source of inspiration for the design of apparel, body adornment and fragrance and, in their natural and faux forms, flowers decorate fashionable bodies and spaces. This visual essay explores how flowers have variously been integrated within a bunch of fashion exhibitions, including Christian Dior: Designer of Dreams (2017–20).

The essay is arranged into three categories: exhibitions for which flowers comprise the subject or sub-theme; those where flowers have been employed as stylistic props and/or comprise part of the mis-en-scene and designer monograph shows. Those selected for the latter are Christian Dior, as fashion’s mid-20th century floriculturist, his floriculturist successor Dries van Noten and fashion’s rosarians Alexander McQueen and Sarah Burton.

Extended captions comprise curatorial statements of intent as expressed on gallery text panels or within catalogues, along with my own critique.

Flowers Decorative and Spell-binding

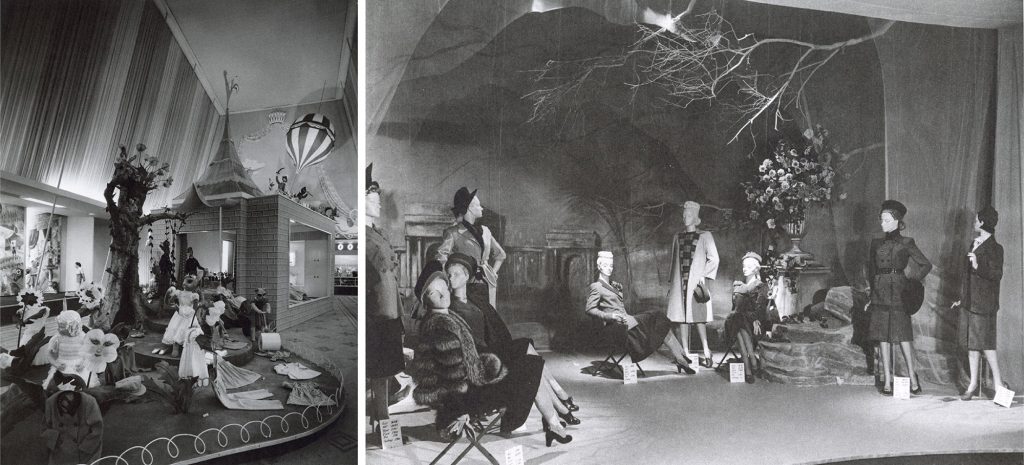

Britain Can Make It (BCMI), Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A), 24 September – 31 December 1946. Organised (it was a trade show, the term ‘curated’ wasn’t used) by the Council of Industrial Design (COID) and designed by James Gardner.

BCMI was a mixed media exhibition which – unusually – comprised a large fashion component. COID’s objective was to present an optimistic vision of Britain’s international role in post war markets. As such, new technologies – rather than the natural world – were foregrounded. Flowers were utilised as props within two areas. A spot-lit bouquet of fake flowers, placed in a, ‘country house’ style, garden urn lent an air of luxury (at a time when fresh flowers were relatively more costly than today) to the ‘Hyde Park Scene’, which showcased women’s exclusive ready-to-wear fashion. More enchanting, were the fanciful flower masks, oversize flower heads and flower decorated, fairy-tale, tree figure incorporated into the children’s clothing displays.

Fashion Inspired Flowers and Fragrance

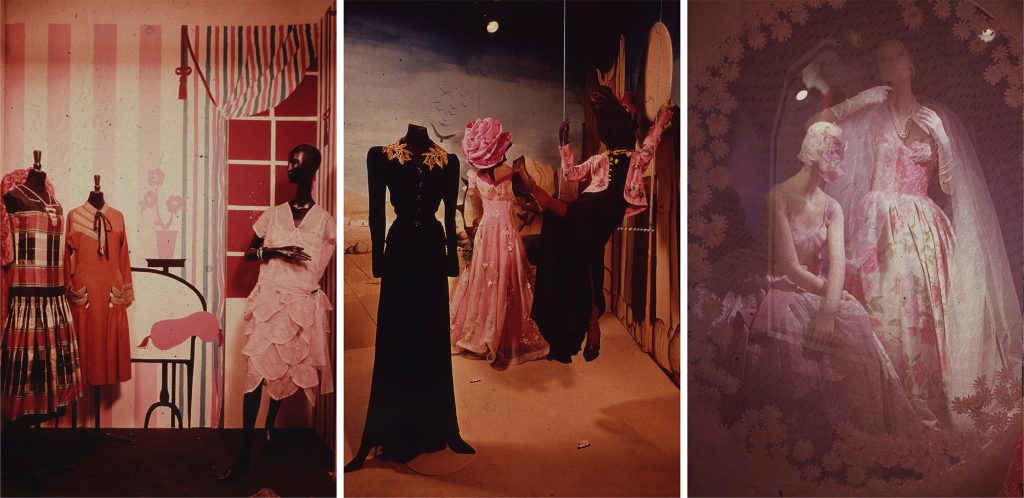

Fashion: An Anthology by Cecil Beaton, V&A, 13 October 1971 – 16 January 1972. Curated by Cecil Beaton. Designed by Michael Haynes, working closely with Beaton.

Flowers featured in three sections of this exhibition staged within a double tier Perspex structure located in the museum’s main entrance. Artist Patrick translated the flower pot appliqué design on Vionnet’s La Fleur afternoon dress (S/S 1920) to decorate the backdrop of ‘The 1920s’ section. In the ‘Schiaparelli and Surrealism in the 1930s’ space, the head of a mannequin, wearing an evening gown (dated 1953 it subverted the subversive theme) with an appliqué design of apple blossom, was obscured by an immense pink fabric rose. The special fixtures for this section were made by Janet Benham, Andrew Logan and Anthony Redmile. Their interventions fed into surrealism’s love of displacement, flower personification and almost certainly referenced Dali’s painting Woman with a Head of Roses (1935) and his collaboration with the designer. ‘The 1950s’ section was veiled by a, light infused, sheer fabric onto which hundreds of fabric daisies were applied. Exhibition invoices reveal that 504 bonded fibre daisies, 500 fire proof daisies and three packs of 42 dozen daisy petals were ordered from Burt Bros of Bow for the show. Throughout the exhibition, the flower experience extended to the olfactory as various designer perfumes, some with floral notes, were sprayed morning and afternoon. They included Christian Dior’s ‘Diorissimo’, which has a bouquet of lily of the valley, the haute couturier’s lucky flower.

Flowers as Subject and Theme

Bloom, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 30th March – 20th August 1995. Curated by Richard Martin and Harold Koda.

A succinct account of the rationale for this beautiful exhibition is provided by the following catalogue extracts:

‘Bloom creates fertile gardens of floral apparel around specific flowers – rose, lily, tulip – and floral subjects, including naturalistic categories, stylized exotic fantasies, black “fleurs du mal,” and a metamorphosed garden of women virtually transformed into flowers.’

‘Prodigal nature has provided many interpretations and ideas, from the chaste economies of Henry David Thoreau to the exuberant fantasies of William Wordsworth. Thus, to perceive the display and disposition of flowers, Bloom is organized – as if with seed packets marking each vitrine – around the patterns of floral representation beginning with the scientific and analytic systems that flourished in Europe in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.’

(Martin, R. and Koda, H., Bloom, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1995: 4.)

Fashion & Gardens: spring/summer – autumn/winter, Garden Museum, 7 February – 27 April 2014. Curated by Nicola Shulman.

Decoration, landscape, colour theory and garden maintenance comprised the four themes for this exhibition, the first devoted to fashion at the Garden Museum. Exhibits included examples of the flower craze for camellias in the 1840s, sunflowers in the 1890s and Mary Quant’s 1960s daisy logo fashions to contemporary flower-like designs by Alexander McQueen, Christopher Bailey and Philip Treacy. Artist Rebecca Louise Law was commissioned to create a flower installation for the gallery space. Over a period of six months, she dried and pressed two thousand wild flowers. Her labour was a tribute to soldiers in the First World War, who picked and dried the few precious flowers that grew amidst the trenches, and tucked them into letters sent home to loved ones. Using copper wire, the artist installed the flowers inverted and suspended from the ceiling to visually striking and atmospheric effect.

Flowers, Politics and the Natural World

Force of Nature, The Museum at the Fashion Institute of Technology, 30 May – 18 November 2017, curated by Melissa Marra-Alvarez.

Force of Nature explored the complex relationship between fashion and nature within the contexts of the arts and natural sciences. It was arranged into ten themes including ‘The Botanical Garden’, ‘The Science of Attraction’, ‘Physical Forces’ and ‘The Language of Flowers’. Below, are texts used for the Introduction and ‘The Language of Flowers’ panel texts.

Force of Nature spans the 18th century to the present, to reveal how the natural world has influenced fashion. The exhibition’s ten sections focus on distinct facets of fashion in relation to nature. Approximately 95 objects from the collection of The Museum at FIT illustrate the complex connections between principles in the natural sciences, such as the dynamics of sexual attraction, and fashion design.

The exhibition alternates between fashions that reference nature, and others that interpret scientific concepts. Included are a Charles James evening gown that transforms its wearer into a sensual flower and an ensemble by Rick Owens that contemplates extinction. Force of Nature concludes with a look at what modern fashion designers are doing to create a sustainable relationship with the natural world. Below is the text panel written for ‘The Language of Flowers’ section.

The Language of Flowers

During the 19th century, many publications explored “the language of flowers. These popular books promoted the notion that the species and colors of flowers held symbolic meaning — prompting, among other things, the exchange of coded bouquets. Yet flowers project a conspicuous duality. On the one hand, they suggest innocence, beauty, and refinement; on the other, as the reproductive organs of plants, they represent sexuality.

In 1735, botanist Carl Linneaus established that plants reproduce sexually, and he promoted a romantic analogy, comparing plant sexuality to human love-making. As one journalist wrote, flowers are “the literal and figurative representation of layered femininity.” Their complex meanings often find expression in fashion.

Fashioned from Nature, V&A, 28th April 2018 – 27th January 2019. Curated by Edwina Ehrman. Designed in-house – senior designer Juri Nishi.

Featuring over 300 exhibits and spanning 400 years, this exhibition explored the stylistic relationship between fashion and the natural world, situated within the critical contexts human labour, ethics and sustainability. Fashioned from Nature was exhibited on two floors within the museum’s fashion gallery. Clever lighting created shadow garlands around hats and headdresses and flower-patterned textiles were displayed alongside and behind dressed mannequins. Dilys Williams, director of the research Centre for Sustainability at LCF (UAL) was a key contributor to the upstairs gallery which explored critical issues around fashion, nature and the environment, within which flowers were not foregrounded.

Fashion’s Floriculturists: Flowers and Symbolism

Christian Dior, Couturier du Rêve, Musée des Arts Decoratifs, 5 July 2017 – 7 January 2018. Curated by Florence Müller and Olivier Gabet. Scenography by Agence NC Nathalie Crinière.

Christian Dior: Designer of Dreams, V&A, 2 February – 1 September 2019. Curated by Oriole Cullen. Scenography by Agence NC Nathalie Crinière.

Christian Dior: Designer of Dreams, Long Museum, West Bund, Shanghai, 28 July 2020 – 4 October 2020. Curated by Oriole Collen. Scenography by Agence NC Nathalie Crinière.

Audiovisual by Light Emotion.

Christian Dior (1905–57) was the mid-20th century’s fashion floriculturist. The haute couturier likened the processes of creating a collection to ‘young shoots which ripen into a thousand flowery patterns’ (Dior by Dior 1957: 64) and his pronouncement that he designed for ‘flower-like’ women is oft quoted. Flower themed fashions, some associated with rites of passage, were exhibited in a dedicated ‘Garden Room’ gallery featuring an installation comprising a profusion of (fire-resistant) laser-cut paper flowers suspended from the ceilings and trailing down the walls. This was the work of Wanda Barcelona, a firm run by Ini Velez Botero, Daniel Mancini and Iris Joval who have a long-term working relationship with Dior. For the Paris installation the trio made 4,500 roses, 4,500 clematises, 1,400 lily of the valley and 700 wisteria vines. Each flower and leaf were folded and glued by hand. The installation took twenty days. The photograph shown here is from the Paris exhibition. In Shanghai, the flower installations were distinctively colourful and luminescent. Below, is ‘The Garden’ panel text from the V&A exhibition.

The Garden

“After women, flowers are the most divine of creations.” Christian Dior, 1954

From early childhood Christian Dior was fascinated by gardens. His mother Madeleine cultivated the family garden that overlooked the sea at Granville, and as a small boy, he loved to study her Vilmorin-Andrieux plant catalogues. In later years he designed a pergola for the garden as a shelter from the sea breeze.

Dior enjoyed sketching his dresses outside in his garden and flowers were a continual inspiration, both for his clothes and the floral accents of Dior perfumes.

His New Look was inspired by the shape of an inverted flower, and the garments were first modelled against a backdrop of large floral arrangements by Parisian florist Lachaume. Flowers abound in Dior’s work – from single silk flower decorations to abundant prints and intricate embroideries.

The garden remains a theme to which successive designers at the House of Dior return. Yves Saint Laurent frequently inserted the rose motif into his designs for Dior. Marc Bohan, Gianfranco Ferré and John Galliano, all keen gardeners, often adorned their collections with floral embroideries. Raf Simons, for his first Dior collection, sent his models down the runway against a backdrop of walls of fresh flowers. For her first collection for Dior, Maria Grazia Chiuri created dresses with hand-dyed silk petals, caught like delicately pressed flowers between layers of tulle.

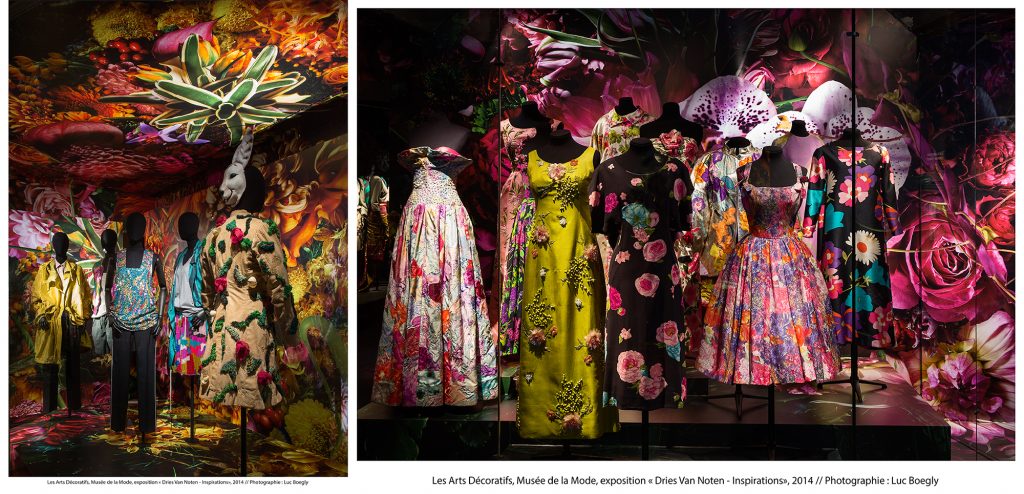

Dries van Noten – Inspirations, Musée des Arts Decoratifs, 1 March – 31 August 2014, curated by Pamela Golbin who worked closely with Dries van Noten. Scenography by Jean Dominic Secondi.

By the late 1980s, Dries van Noten (b.1958), the Belgian designer revered for his refined and innovative floral textile prints, embroideries and intense colour palette, had assumed the role of fashion’s floriculturist. The designer’s Spring/Summer 2017 collection was presented on a catwalk amidst immense ice blocks containing suspended flowers, sculpted by Japanese flower artist Azuma Makoto. The exhibition Dries van Noten – Inspirations presented Dries van Noten’s signature flower-themed fashions displayed within environments decorated with vinyl printed with techno-colour designs of lush, oversize, flowers and foliage. A space titled ‘Bouquet’ included dresses by Balenciaga, Dior and Cardin which had inspired van Noten (a rare tribute for a designer to make). In the menswear section, Cecil Beaton’s 1937 Easter fancy dress costume, comprising an 18th century style coat with muslin roses (and plastic egg shells) worn with a rabbit mask (borrowed from the V&A) was displayed alongside flowery male attire. (Flowers were a prominent form of decoration on elite fashionable 18th century menswear, but by the 19th century – within a climate when flowers were often gendered feminine – flower patterning became more discreet, taking the form of a fresh flower boutonnière, flower patterned waistcoat, braces or handkerchief. By the late 1960s flowers were prominent within male hippy fashions and were revived on the international catwalks from the early-1980s).

Roses, Alexander McQueen flagship store, 27 Old Bond Street, London, November 2019 – ongoing. Co-curated by Sarah Burton and Sarah Mower.

Alexander McQueen (1969–2010) holds the mantle of fashion’s rosarian and Sarah Burton (b.1974) – for whom roses also hold special meanings – continues in his wake. This intriguing exhibition reveals insights into the processes of design and complexities of making rose themed fashions, alongside displays of completed garments. Research boards include photographs of studio team visits to famous Sussex gardens alongside fabric swatches inspired by the flowers observed. Displays of artificial roses made in varying colour tones and sizes are shown on boards with annotated notes about which were selected and why and insights re provided into the complex processes involved in manipulating huge whorls of fabric to create rose-like forms for dresses and tailored apparel (the latter described as ‘hybrid roses’ as they combined elements from tailoring and dressmaking). A series of booklets, including Roses, which sadly are not available to purchase, are available or visitors to read. They are placed on a studio cutting table where practical masterclasses and workshops also take place.