A review of an exhibition is a sort of rational anamnesis, a personal recollection. While some pragmatic questions arise in the mind of the reviewer – Who is the curator? What was their aim? How was the exhibition designed? – other more personal memories start to re-emerge. Which day did I see the expo? How did I experience it? Did I see the exhibition with someone? What did we talk about? Indeed, an exhibition does not only exist in a physical place. An exhibition remains in you, as you begin to ‘see’ an exhibition long before the very moment of the physical visit. We may first learn about an exhibition online, looking at images of it. People may suggest that we go and see an exhibition or we may stumble on it. Especially in this digital era, we visit an exhibition in multiple ways and our decision to see an exhibition live may also depend on the ways in which the exhibition is presented online. Paradoxically, these initial clues become after-remains of the expo and merge with our lived experience of it.

In the case of the exhibition Atelier E.B. Passer By, this logic resonates well. This is not only due to the large amount of paratextual materials created around the exhibition (both digitally and analog but for the very essence of the exhibition that challenges ontologically the temporality and the nature of an exhibition. Atelier E.B. Passer By shows how exhibitions can be “machines à penser”, [1] devices that position and invite visitors into an imaginative state. Therefore, my intention to write this review on Atelier E.B. Passer By at Lafayette Anticipations, is not to didascaly draw the reader a picture of the physical exhibition. Rather I want to mirror the freedom that Lipscombe and McKenzie stage in their exhibition and demand of the visitor, recollecting my experience of it; mobilizing various connections and evocations that the exhibition triggered in me before, during and after the physical visiting of the exhibition.

I.

I first learned about the exhibition in a cab with Antoine Bucher, a friend and colleague who started with Nicholas Montagne, the online bookshop Diktats. We were coming back from a conference titled ‘Fashioning Art History’, at the Institute Français de la Mode (IFM), on methodologies between fashion studies and art history. There I spoke about fashion remains and ephemerality and, before me, Amy de la Haye discussed, amongst other things, the challenges of reviewing fashion exhibitions. Back in the cab, Antoine and myself continued the discussion on fashion curating as he began describing the exhibition Atelier E.B. Passer By that, at that time, was held at the Serpentine Gallery by duo artist Lucy McKenzie and designer Beca Lipscombe. Antoine was thrilled that the expo was coming to Paris at the new space, Lafayette Anticipations, designed by the architect Rem Koolhaas. He began explaining the exhibition, telling me that he loaned some of his historical document for the exhibition while enthusiastically narrating an anecdote on how McKenzie wanted to feature the painting Trial and Error (1939) by Meredith Frampton (b. 1894, d. 1984) conserved at Tate Britain. When refused the loan, McKenzie, continued Antoine, decided to create a copy and showcased it in the exhibition. This story immediately caught my imagination. To stage and humorize the pitfalls of institutional power, access and control seemed a witty reflection on institutional boundaries, offering the possibility to transform restrictions into opportunities in a curatorial project. Being intrigued by Antoine’s hints on the expo, I immediately began to research it on the Serpentine Gallery website and early reviews of the show (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 Screenshot of the webpage on the exhibition Atelier E.B. Passer by – www.serpentinegallieries.org/exhibitions-events/ateleier-eb-passer

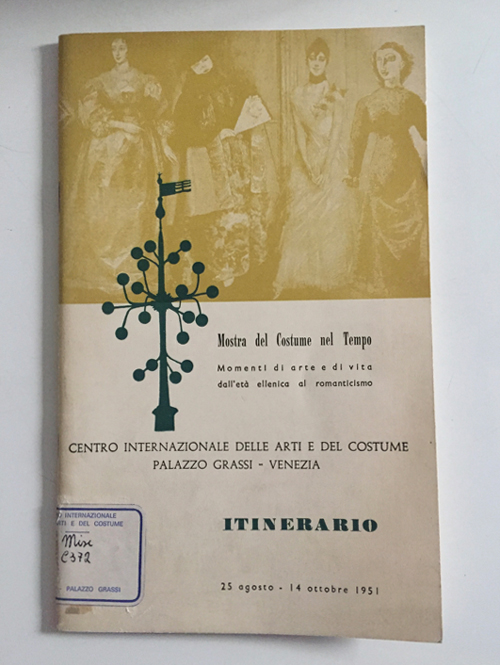

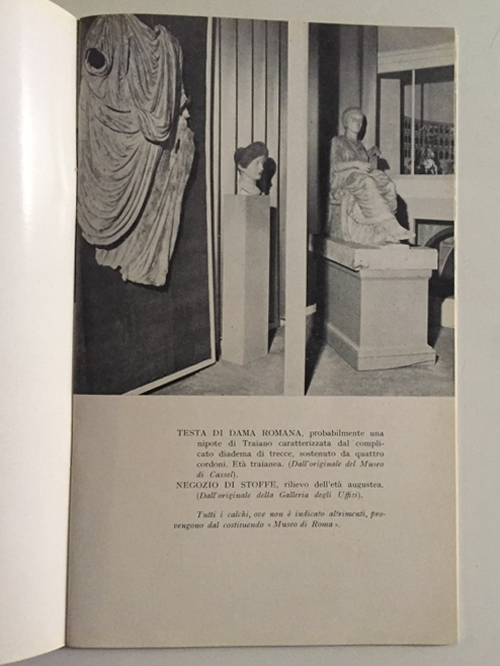

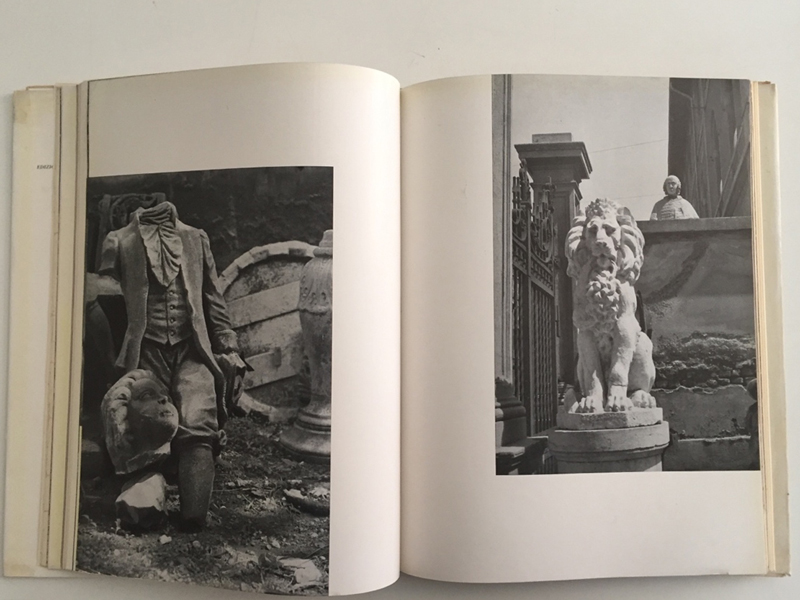

Fig. 2 – 3 Catalogue of the Exhibition Mostra del Costume nel Tempo. Momenti di arte e di vita dall’età ellenica al romanticismo, Centro Internazionale delle Arti e del Costume Palazzo Grassi, 25th August – 14th October 1951, Venezia

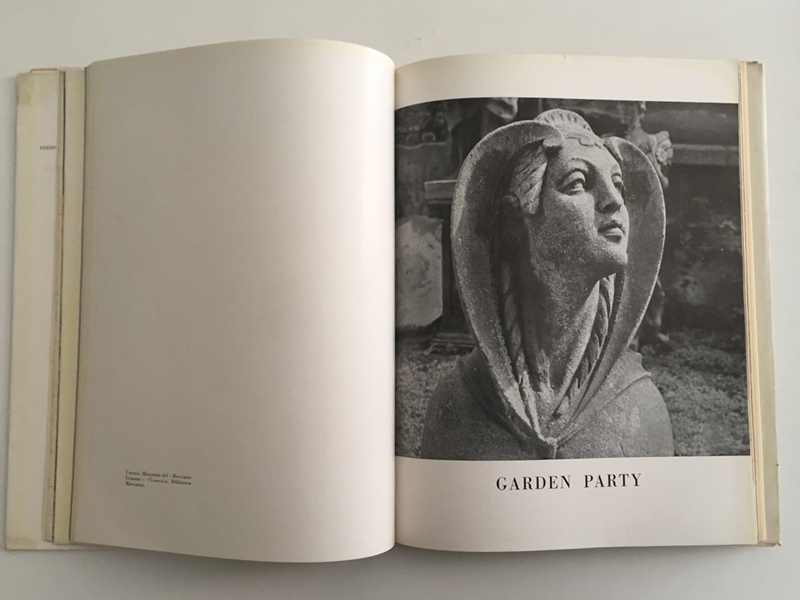

The vision of this sculptured dress fascinated me as it seemed to act as a metonym for the relation between fashion and time in museums, the paradox of ephemerality of garments but also the necessity to hybridize techniques and paradigms of showing the dressed body in exhibitions. Here the sculptured dress is full but empty, bodyless. Thinking about this sculptural tableaux, the words of Atelier E.B came to mind: “ We want to highlight the ‘dressed’ aspect of the statues, the artists draw attention to the fundamental similarities between sculpture and mannequins, and their equally pronounced differences”. [2] While Atelier E.B were here referring to their sculptural installation, these words created a liaison between these two images and these exhibitions. Both exhibitions and the sculptural installations seemed to speak a similar language. Both were fashioned to highlight disciplinary dialogues while reflecting a modernist reflection on fragmentation, remains of bodies and techniques of exhibition-making. The carnality of the statues and their decay in the CIAC’s catalogue resonated when rethinking of the sleek images I was looking at online from the Serpentine Gallery installation. The image of the CIAC exhibition’s headless sculptured dresses or even the photographic series ‘Party in the Garden’ created for another book by CIAC for the same exhibition, created a counterpart connection with the fragments, heads and missing body presented by McKenzie and Lipscombe (Fig. 4 – 5).

Fig. 4 – 5 “Garden Party”, Photography by Pietro Donzelli, Arti e Costume. Rassegna Semestrale del Centro Internazionale delle Arti e del Costume in Venezia a Palazzo Grassi, Venezia: Edizioni Internazionali d’Arte, 1951.

As McKenzie suggests in the brochure’s glossary:

“In the context of sculptural practice […] the disfiguration of the human form is not only acceptable but positively celebrated as an aesthetic gain. This is particularly true of the treasures of Classical Antiquity, the fragmentary state of which signifies value in a variety of other ways, including their authenticity as relics that have suffered from the destructive effects of time. The vulnerability of their surfaces – whether of stone, marble or plaster – is in direct contrast to the durability of the plastic used in a mannequin, as is the rich history inscribed in their battered and broken condition”.[3]

This archaeological sentiment was mirrored, in a completely different way, in the second image that caught my attention: the window of a shop titled ‘atelier e.b’ (Leading image). Inspired by a shop window initially facing passers-by in Ostend (Belgium), this Faux Shop stuck in my mind until the day I saw the exhibition in Paris. Was this a real shop? Or an attempt to excavate a forgotten one?

II.

Once the exhibition opened at Lafayette Anticipations, I understood that these digital glimpses represented only a small part of the experience. What I saw online and through the words of Antoine was now reflected in front of me in a space that seems to perfectly suit the ambition of Atelier E.B. Created in 2013 as a Foundation of the Groupe Galeries Lafayette, the institution hosting the expo added, in fact, another layer to the exhibition, provoking an interesting reflection on the role of ‘space’ in the making of the exhibition, but also on the ways in which commercial enterprises curate their own legacy and are increasingly merging commercial and artistic purposes. Atelier E.B. Passer-By perfectly staged these tensions, reflecting on the porosities between the commercial and the artistic, the authentic and the fictional, responding to the current forms of privatization within public institutions and the necessity to recalibrate our judgment and vision of what museums, galleries and cultural institutions may be today. To borrow the words of art critic Francesco Bonami:

“A contemporary institution should be a temporary point of transit for visions that may also contradict its identity, and which can, in their contradictions, take part in the inevitable and necessary process of transformation.”[4]

Atelier E.B. Passer By embodied these transitions and projected the visitors into the strengths and the pitfalls that have characterized the discourse about fashion in museums. The exhibition was caught in a constant in-between, as its makers. The exhibition was an exhibition, a shop where you could try and buy or order the duo’s collection, an artistic intervention, a reflection on fashion curating, a group show, and a space of encounter where you could speak to Lipscombe and McKenzie. Each piece/installation in the space was a calibrated action, capable of instilling uncertainties into visitors. This became evident from the very beginning as you were faced, at the entrance of the show, with the ‘Faux Shop’. Created by artist Steff Norwood for the Serpentine Gallery exhibition, the installation was rebuilt for the Paris venue and presented the designers’ Jasperware collection. The intention, once again, seemed multiple. The window functioned as temporal shell to transport the visitor. Rather than a cabinet of wonder, it seemed an act of archaeological restoration of commercial displays, early merchandising techniques and consumption in urban spaces: hopefully a territory of future exploration in fashion curating.

The shop also served to display the collection. In this way, these contemporary pieces were freed from current techniques of displaying garments in exhibitions and encapsulated into an old aesthetic of visual merchandising where garments are floating with the support of transparent threads and needles. Sold in the showroom placed behind the window where visitors could also try on the pieces, the collection reinvigorated a discourse on imitation, mimesis and reinterpretation that characterized neo-classical art and its philosophy. Exceeding ideas of copying, the collection and the exhibition become a hymn to this mimetic attitude: from its title recalling Wedgewood Jasperware porcelain, to the depiction on sweatshirts of Greek statues and Roman shields. Beside the collection, was placed the fore-mentioned copy of Frampton’s painting, a series of publications and a Marie Laurencin inspired painting, made by McKenzie, featuring the Jasperware collection: another way to displace and make the visitor/customer wonder about authenticity and time (Fig. 7). Both the shop and the showroom staged the intriguing and subjective way in which Lipscombe and McKenzie flirt with the languages of art, neoclassicism and fashion via an astute discourse on commercialization of bodies and commodities.

Fig. 7 – Image of the exhibition Atelier E.B. Passer by, 21 February – 28 April 2019, Paris: LaFayette Anticipations, 2019

Fig. 7 – Image of the exhibition Atelier E.B. Passer by, 21 February – 28 April 2019, Paris: LaFayette Anticipations, 2019

III.

At the centre of these multi-disciplinary flirtations was the mannequin, used as archetype able to aggregate multiple discussions on the history of exhibitions, politics of the body, artistic interventions, commercial display practices, and fashion. The mannequin was a constant presence and it took a central role on the ground floor where it appears in ‘flesh-and-bones’ or in representations of boutiques or exhibitions. The discourse on the role of the mannequin continued on the second floor where pieces from the Atelier E.B collection were presented on mannequins created by Tauba Auerbach (USA), Anna Blessmann (GER / UK), Marc Camille Chaimowicz (UK), Elizabeth Radclifffe (UK), Bernie Reid (UK), Markus Selg (GER) and Steff Norwood (UK). All artists were invited to interact with the collection and propose a way to display playing on scale and humour, sexuality and race (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8 – Image of the exhibition Atelier E.B. Passer by, 21 February – 28 April 2019, Paris: LaFayette Anticipations, 2019

Atelier E.B. Passer By gathered complex narratives on the mannequin via associative thinking and subjective actions. Lipscombe and McKenzie here worked as artists, historians, curators, designers, commissioners and even guides to the exhibition. In this sense, the display of these mannequins as ideals recalls a surrealist exercise where artificial bodies are staged as more than just commercial props but rather as symbols of anthropomorphic interconnections. Lipscombe and McKenzie’s visual and material aggregation evoked the method used in the “corridor of mannequins” at the Exposition Internationale de Surréalisme (Paris 1938). My reference to this exhibition is not casual but it seems aligned to the surrealist attention given to mannequins in International Exhibitions as also evidenced by the documentary research presented by Atelier E.B at Lafayette Anticipations. Here an entire section showcased brochures, catalogues and ephemeral souvenirs from the Brussels International Exhibition 1935 mixed with commercial ads and various ephemera about the Department store ‘Lafayette’ loaned by the Lafayette archives. This section, more than others, seemed to dialogue with a recurrent and contemporary visual use of ‘the historical’. This display became Warburg-arian tableaux, mixing official and unofficial documents as a way to propose new narratives (Fig. 10) of displaying the body.

While these artistic historical interventions perform a freedom that many curators may not experience in museums, they also function as reminder of subjective practices or, to use de Certeau’s words, of historian’s “gesture of setting aside, of putting together, of transforming certain classified objects into “documents”. [5] It is this impulse that generates questions about Atelier E.B’s uses of ‘the historical’. Is the duo of artists/designers/curators asking an imaginative exercise from the visitors (and from themselves)? Is there a sort of denunciation of institutional curatorial power? Or both? The physical presence of the designers in the exhibition space reinforces these uncertainties. Their presence may be seen as an act of interpretational control but also as an opportunity to inhabit exhibition spaces as sites of creation and exchange. Intentionality and authenticity are here haunted and performed, and therefore questioned. The tangible epitome of this attitude in the exhibition were the central wooden stairs connected the two display floors. Constructed by Les Ateliers Majorelle, it was built to showcase the railing of Lafayette’s staircase created in 1912 by the architect Ferdinand Chanut and now conserved in the Company’s’s archive – which was evoked by the archival inventory number tag attached to the rail. In the exhibition, the rusted steel staircase is re-activated, made alive again. Exhibition visitors could walk and brush their hands over it, as Lafayette’s visitors did in the early twentieth century. The stairs become more than a device connecting the two floors, but a vector of time, a transformative tool that transmuted visitors into consumers, the past into present, the commercial into the artistic.

IV.

Such an explicit artistic attitude towards the transformative nature of the historical and the archival is not a novelty, but it comes at a time when filmmakers, performers and designers are increasingly invited to act as curators or historians – see for example Wes Anderson at the Kunsthistorisches Museum of Vienna or Francesco Vezzoli at Musée d’Orsay. In this context, this type of artistic historical narrative stands as both an invitation and a reminder of a subjective freedom that characterizes the function of interdisciplinary dialogues between art, fashion and design in redefining what history (and maybe curators) represent today: something that has historically ‘troubled’ the presentation of fashion in museums since the advent of Cecil Beaton at the V&A (1971) and Diana Vreeland at the Costume Institute (1972). As Harold Koda and Richard Martin note, Vreeland “freed costume exhibition to participate in the new subjectivity of history and a new joy of delighted spectatorship”.[6] In Atelier E.B. Passer By, these two variables are not only made evident but also restored via a discourse on the practice of exhibition making, the staging of fashion exhibitions’ documentation or performances like Lynn Hershman Leeson, Stills from 25 Windows: A Portrait of Bonwit Teller (1976) (where mannequins move between commercial, urban and artistic spaces in the city of New York). The exhibition, to use McKenzie’s words, was also presenting an “unrealiable” history of exhibitions and displays, making me wonder on the potential of this exhibition to be a reliable testimony of the flaws and difficulties regarding historical reconstruction in museums. While this may sound as a provocation, it is also what the installation seemed to propose. The point is not to look at this exhibition as a fashion exhibition, an art exhibition, an archaeology of commercial display. What really emerges is that the exhibition is actually suggesting “passer by” as a method: a reflection on a way of doing research, a way of invading disciplines, a way of looking at the past and the present, a way of making, a way of visiting an exhibition. And maybe even a way of reviewing it.

[1] I refer to the exhibition ‘Machines à penser’, conceived and curated by Dieter Roelstraete, 26 May – 26 November 2018, Fondazione Prada, Venezia.

[2] www.serpentinegallieries.org/exhibitions-events/ateleier-eb-passer

[3] Lucy McKenzie, « Power-sharing with the Muse », Atelier E.B. Passer-by, Brochure of the exhibition, 21 February – 28 April 2019, Paris: LaFayette Anticipations, 2019

[4] Francesco Bonami, “A world of Fleas and Elephants, Collective Space and the Crisis of the Museum as Industry”, in Total Living, edited by Maria Luisa Frisa, Mario Lupano, Stefano Tonchi, Edizioni Charta: Milan. 2002, 391.

[5] Michel de Certeau, The Writing of History, Translated by Tom Conley, New York : Columbia University Press, 1998, p. 73.

[6] Richard Martin, Harold Koda, Diana Vreeland: The Immoderate Style, catalogue of the exhibition, December 1993 – March 1994, New York: The Metropolitan Museum.