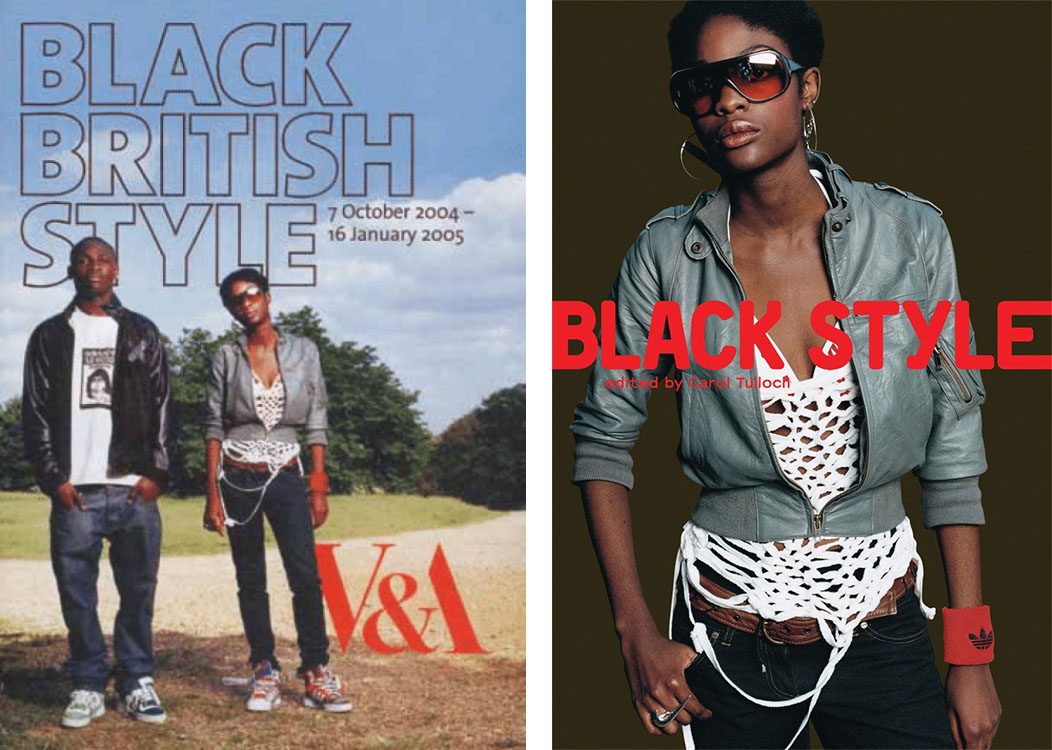

Black British Style was co-curated by Carol Tulloch and Shaun Cole at the Victoria & Albert Museum in 2004-05. It was the first major exhibition in a national museum devoted to showing the dress practices of black people in Britain from the late 1940s to 2004 as they confronted the tenets of different to present a sense of ‘authenticity’ to their lived experience. It builds on previous V&A exhibitions: Streetstyle: From Sidewalk to Catwalk, and From 1945 to Tomorrow (1994-5) as well as associated publications.

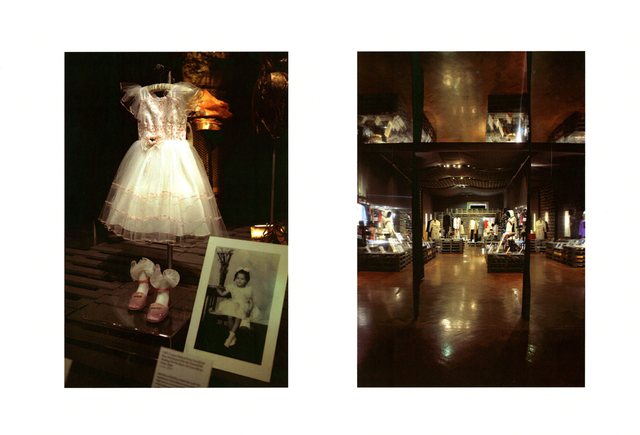

It brought into being for me, how and why black men, women and children styled their bodies in post-war Britain, through migration, religious, secular or political activities, and the dress choices and practices, sartorial aesthetics, as well as embodied dignity and aspirations for respect. The exhibition was curated with care towards the material culture of garments and accessories contextualized by archive photography, film, and oral testimonies. Revisiting Black British Style through the lens of the present, raises questions about representations of dressed black body now as the internet develops.

Black style is a complex commodity, and the dressed black body exposes the complexities of blackness, which in Black British Style speaks to people of the African diaspora who share the legacy of the rupture and trauma caused by Transatlantic slavery. Black style tends to conjure images of black youth and the street, but there is more to black life than this, such as everyday dress, occasional and traditional clothing. There is also an archive of black styles including garments and looks, such as the black beret and leather jacket styling of the Black Panthers reclaimed by contemporary Black Lives Matter protesters. Black style cannot simply be defined as on a black body, with questions of appropriation and commodification as enacted through social media. Nor is it simply what is worn, but how it is performed with an individual walk, gesture, and even patter. Black dress aesthetic draws on contemporary and historical references from across the African diaspora, and influenced by factors and pressures around Western culture, urban prowess, group affinity, pleasure expressing femininity, masculinity or sexuality, and the desire for the ingenuity of designer clothes.

Crucially, black style expresses collective and subjective cultural identity in the dignity of dress as an agent of self-respect and human dignity, which echoes what Rex Nettleford called ‘smaditisation’ in the ways the Jamaican underclass expressed selfhood through clothing. Dignity agency through dress resists essentialist stereotypes of black style by foregrounding a plurality of lived experience. The African-American scholar and activist W.E.B. Du Bois argued that individuals who do not protest against injustice are likely to lose a sense of their own dignity. In this spirit, Bernard Boxhill sees dignity as a subjective display demanding respect and equity from oppressors who see otherwise, such as those of the Windrush generation who find themselves treated as illegal immigrants, incarcerated and deported. In soothing their personal trauma, they hold their heads with pride because they know that the dignity displayed in their dress when they arrived is the same as now.

Music shapes black life, and it is the background beat to Black British Style, because it brings people together to soothe the trauma of racial brutality, whether that be religious or secular music. These may be contrasting spaces, but unlike white culture, they represent the uniqueness embedded in black expressive culture that connects the spiritual with political and the sensual, such as the gospel music and Rock ‘n’ Roll electric guitar playing of Sista Rosetta Tharpe, to the erotic spirituality of Marvin Gaye and Prince. This is also evident in the dressed styles of black funerary rites across the African diaspora, where respectability hegemony towards ‘correct’ forms of attire sits alongside more conspicuous more dress that together celebrate the life of the deceased allowing the spirit to see properly what is being mourned for.

The aesthetic poignancy of Black British Style resonates in the twenty-first century, where heredity and traditions of style accumulated over more than 50 years, shaped in part by the politics of race and ethnicity, evoke visual pleasure and invoke possible futures, which testifies to the black permanence in Britain.

© Dr. Michael McMillan – June 2021