The Costumes of Royal India

Exhibition dates: December 20, 1985 – August 31, 1986

Press Preview: Monday, December 9, 10 a.m. – noon

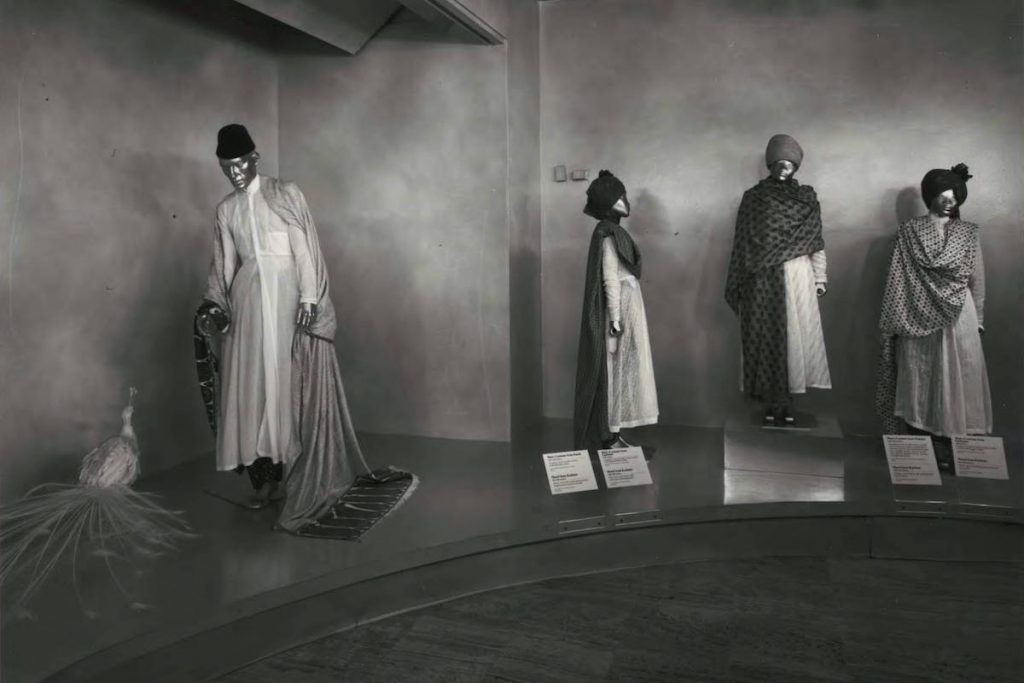

The riches of the fabled courts of India are coming to The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Costume Institute. This year’s exhibition, the 14th annual Costume Institute exhibition to be organized by Diana Vreeland, Special Consultant to The Costume Institute, is Costumes of Royal India. It will present a lavish selection of gorgeous and elaborate state and court costumes from twelve of the most important former princely states of India, among them, Baroda, Hyderabad, Jaipur, Jodphur, and Kashmir. Also included will be a selection of saris from the states of south India, including Mysore and Travancore. Most of the court costumes and textiles in the exhibition date from the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries and have been lent from the private collections of some of the former ruling families of India. The exhibition will also include accessories (fans, turbans, footwear, jewelry), furniture, bolsters and other luxurious furnishings of court life, and fulllength royal portraits.

Costumes of Royal India has been made possible by The Christian Humann Foundation and Ratti S.p.A. Additional support has been received from Air India and Mr. and Mrs. Vincente Minetti. The exhibition is part of the nationwide Festival of India, organized jointly by the Government of India and the Indo-U.S. Subcommission on Education and Culture. In 1858 Queen Victoria was proclaimed Empress of India, but nearly half the area of the entire subcontinent continued to be ruled by autonomous Indian princes who were known by such royal titles as Rajah, Maharajah, Rana, Maharana, Nizam, and Nawab.

More than 600 princely states scattered across the length and breadth of India were ruled from massive fortified palaces by some of the most colorful personages in Indian history. These princely houses traced their lineage back to the great Hindu dynasties of medieval India. Some, like the Rajputs (meaning “sons of kings”), whose many separate clans governed powerful kingdoms in Rajasthan and Central India, went so far as to claim descent from the sun and the moon. The Indian princes retained varying degrees of autonomy from the successive Muslim empires that were established in northern India after the eleventh century. Their courts were the strongholds of traditional Indian culture, but after the seventeenth century they were increasingly influenced by the dazzling court culture of the Mughals, the last and greatest of India’s Muslim dynasties. The most remarkable feature of the Indian states was their diversity. At one end of the scale there were such fabulously wealthy kingdoms as the “Dominions of the Nizam of Hyderabad and Berar,” whose 82,700 square miles dominated the tableland of the Deccan. At the other end were minute holdings in Western India amounting to no more than a few dusty villages and yielding revenues of a few hundred rupees. As a result of these disparities — great distances separating many areas, geographic contrasts, varigated terrains, and the sizes of the states themselves — many regions over the years developed their own traditions, customs, and styles. The exhibition, Costumes of Royal India, is designed to suggest this diversity of the royal courts of India. The Indian royal palaces likewise varied in size and style. Most of them were enormous and wildly exotic structures: Cooch Behar’s Renaissance-style building, for example, was dominated by a dome modelled after St. Peter’s in Rome, while the Jagajit palace at Kapurthala looked to Versailles for its inspiration. When the Maharaja of Idar first visited England, he was startled to see how small Buckingham Palace was in comparison with many Indian palaces.

Inasmuch as the sovereign personified the state, the richness of his garb and the opulence of his court and entourage were the pride of his subjects. Therefore he showed himself to his people in royal audiences and on ceremonial occasions in full magnificence as often as possible. Travelling out of the state for royal hunts or military campaigns or up to the hills to enjoy the cold weather was an important and time-consuming royal pastime. Historical records from the seventeenth century tell us that to service a short journey the camp required 100 elephants, 500 camels, 400 carts, 100 bearers, 500 troopers, 1000 laborers, 50 carpenters, tent-makers, and torchbearers, 30 leather-workers, and 150 sweepers. In the late nineteenth century, travel to Europe was equally fraught and laborious. Passenger liners were often chartered to carry huge silver urns of Ganges water for drinking and bathing and an entourage that included barbers, musicians, cooks and, on occasion, even buffaloes to maintain a supply of fresh milk.

Costumes of Royal India will include about 150 complete royal costumes, many of which are made up of several different layers and items of clothing. On view will be several complete outfits for children — duplicates in miniature of the adults’ splendid and elaborate dress. One section of the exhibition will show the many styles of the turban. Another area will be devoted to shoes and slippers, some of them heavily embroidered and bejewelled, some made entirely of silver, gold, and ivory. A high point of the exhibition will be a life-size elephant supporting a howdah, lavishly decorated and painted and hung with jewels. Indian textiles form an important aspect of the exhibition, for India has been preeminent for more than 2000 years in the production and export of textiles. Indeed, India was the original home of cotton, just as China was of silk. The impact of Indian fabrics on the Engligh-speaking world is testified by such household terms of Indian origin as calico, chintz, shawl, pyjama, gingham, dimity, and bandana. In the exhibition, alongside costumes of cotton net from Lucknow (center of cotton production), silks and brocades from Benares (home of the Indian silk industry), hand-painted and tie-dyed muslins, woven wools from Kashmir, diaphanous cotton mull, and clouds of delicate gold and silver tissue will be seen costumes of such heavy gold and silver embroidery and precious jewels that a man can scarcely stand under them.

As in previous Costume Institute exhibitions, a specially prepared musical tape will be played continuously in the galleries. The music this year will be traditional music of India. Mrs. Vreeland has selected sandalwood scent (which has been specially prepared by Guerlain) to be sprayed in the galleries every morning. The exhibition is being organized by Mrs. Vreeland with Stephen Jamail and the staff of The Costume Institute. The installation was designed by David Harvey, Designer for the Metropolitan. The installation lighting is by William L. Riegal, Museum Lighting Designer. Martand Singh coordinated plans in India for the exhibition. A book, A Second Paradise, by Naveen Patnick, illustrating the exhibition, edited by Jacqueline Onassis, is being published by Doubleday. It will be available at the exhibition. A checklist of the contents of the exhibition will also be available.

FOR FURTHER INFORMATION please contact John Ross, or Berenice Heller,

Public Information Department, The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Tel: (212) 879-5500

November 1985

Image provided by The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Thomas J. Watson Library